October 2023

Pierluigi Masini

Genius Loci

I asked a friend, "If we talk of vision who do you think of?" He replied smiling: “Elon Musk”. Musk is the visionary par excellence today, as Steve Jobs and Sergio Marchionne were before him. Of course we acknowledge his intuitions about electric cars were brilliant, but we cannot say the same of some of his other inventions and gambles. Careful then: what does it really mean to have vision? Is vision a trait that is only connected with the personal sphere and the result of genius? Or is it something we can achieve by applying ourselves and studying? And how much influence does genius loci have? Or rather, how are individuals influenced by the characteristics of the place they are born?

As these questions span in my mind I remembered a small painting, seventeen centimetres square, painted by Raphael in 1503, and that now hangs in London's National Gallery. The painting is called "The Vision of a Knight" or "Allegory" and depicts a young man in armour lying asleep on the ground with a beatific expression, his body across his shield, and two young female figures to either side of him. The iconography is unusual and thus intriguing. The theme, philosophical in nature, references Florence under the Medici family and their Neoplatonic Academy in Careggi. This was a circle of intellectuals, architects and artists founded by Marsilio Ficino in the second half of the fifteenth century; a place of scholars who loved to debate - among other things - the difficult balance humans must look for between soul, which tends to elevate towards God by nature, and body, perennially inclined towards sin.

The theme Raphael is working with has its origins in "Somnium Scipionis", the final part of the sixth book in Cicero's "De Republica", in which Scipione is forced to choose between Virtue and Pleasure. In fact our knight in the painting is depicted between Pallas on the left, bearing a sword and a book which are symbols of active military life and study (Virtus), and Venus on the right who, by handing him a flower, invites him to abandon himself to her (Voluptas). The knight lies between the two figures, dreaming in the arms of Morpheus, suspended in a world that exists for only a few hours in the stillness of the night.

In Neoplatonic philosophy, which had its greatest driving force in Florence, human beings find self-realisation by balancing virtue and pleasure, Virtus and Voluptas: they must find ways of making instinct and reason, body and soul, coexist. They have to find their way while walking on a thin knife-edge.

Now here's the thing. What the knight is realising in his dream, what he can see in his mind's eye, is a vision, which when he awakes will lead him to work for good, starting out on a journey that will guarantee the highest end, the immortality of his soul. For the Neoplatonists vision is a message that comes in dreams, when the soul is pure and free of conditioning by the senses.

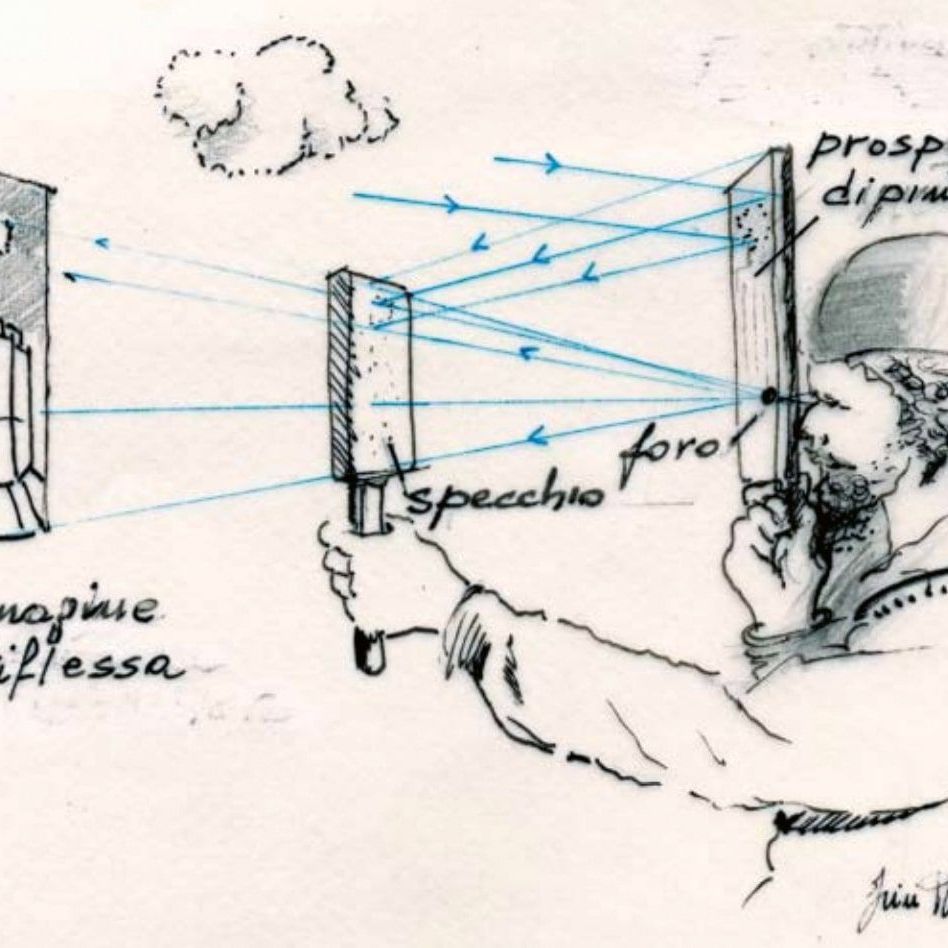

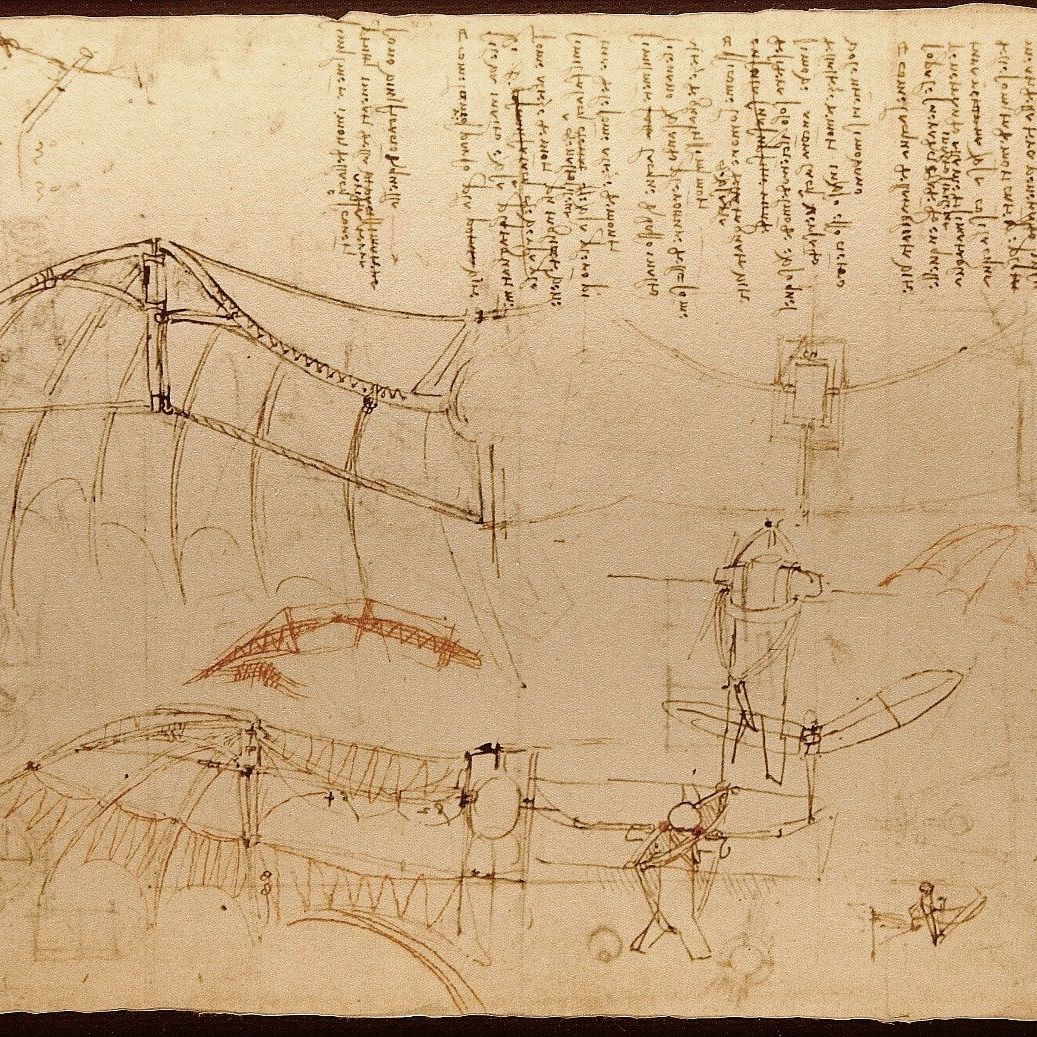

I have mentioned Raphael but we cannot forget that in the same years of the early sixteenth century Leonardo also returned to Florence to work, inhabiting this same environment of speculative study. Leonardo the genius, who had already made an important mark on Milan, attracted several artists to Florence curious to see his works. He was occupied with the large Battle of Anghiari fresco in what was then the Sala del Gran Consiglio in Palazzo Vecchio. He preferred the technique of encaustic to that of true fresco painting and used a thick viscous paint of coloured pigment mixed with wax and oil. Despite the enormous fire pits his assistants directed towards the wall in a race against time, it was difficult to dry the painting - impossible in fact. Inevitably, paint dripped to the floor and colours faded. Leonardo the genius had experimented and failed, just as he had done a few years before in Milan's Santa Maria delle Grazie convent in fresco of The Last Supper. Several decades later Vasari would be asked to cover over Leonardo's battle with another one, which we can still see today.

Leonardo returned to Florence that same year. At 51 he was by now an established painter. Having served under Valentino in Romagna he had finally found a refuge in Pier Soderini's newborn Republic. Soderini had also summoned a young artist Leonardo would never get on with called Michelangelo. While working on the Palazzo Vecchio fresco Leonardo also turned his hand to what would be his most famous work; a portrait of Lisa Gherardini, and the wife of Francesco Bartolomeo del Giocondo (hence the Italian name Gioconda for the Mona Lisa).

If we think of Brunelleschi, and Piero della Francesca, and the invention of linear perspective, and then of Leonardo, who touched such a vast repertoire of activities, and finally the new visual languages of Raphael and Michelangelo, we are confronted with such an explosion of innovation we might think it must have been favoured by the unique, vital and recognizable element that the ancient Romans called genius loci.

The genius loci was a sort of small spirit connected with place, who had to be constantly appeased with offers in order not to become angry, but the expression came to be used to identify certain personalities connected with a specific territory. Certain innovations, certain singular expression of vision, are favoured by the genius loci. That is to say, they could only happen in that specific place.

Tuscany is an example. Giampaolo Nuvolati, an observant sociologist, has studied the aspect of creativity in relation to local area for some time, and recently posited a relation between flatlands and the myth of speed with reference to northern Italy's Po Valley landscape, into which both Enzo Ferrari and Ferruccio Lamborghini were born. Or between Murano glass, reverberating and alive, and the transparencies and iridescence of reflections on the Venetian lagoon. Genius loci is basically something we carry around with us, an ancient spirit that dwells inside us, giving us our sense of beauty and proportion, of shape and colour. And in a shift from aesthetics to ethics Nuvolati also reveals a line between what is right and what is wrong.

But let us return to our idea of vision, which has gone from being a personal intuition to becoming the perspective a company works with: what the company would like to be, its dream. A vision is only achieved through execution, the daily step-by-step work of arriving at the objective we have imagined. However this is not enough: it must go together with an the obstinate determination that is capable of transforming dreams into reality. It is Walt Disney's motto - if you can dream it, you can do it - that turns us into children again, pure like the purity of the knight's soul.

Since we are writing on the pages of the glossy Edra magazine it is natural for us to comment on Edra. What vision does Edra offer? What has Edra achieved since its foundation 36 years ago? And might genius loci have a role in this?

To my mind Edra's vision can be summed up in a few words: to create sofas and furnishings that defy time: products that do not follow trends but that are capable of keeping their character and beauty for an extended life cycle. There is some risk in this, and it goes against the grain of the built-in obsolescence, sometimes more sometimes less, that our society of mass-market consumerism has accustomed us to.

Edra offers solutions for living that take on an emotional character, products destined to stay with us and be handed down from one generation to the next, like family jewels, watches, antique furniture and all the things we hold dearest, the things that surround us and that we wish to survive us. If objects have a soul, and for me in some way they do, then their soul must aspire to immortality, just as we saw in the "Vision of a Knight". Putting this kind of vision into practice requires a large dose of innovation. Dino Gavina, a founding father of the concept of Beautiful Design, observed that, "what is truly modern is worthy of becoming antique".

On the road to implementing this vision Edra has developed in multiple coherent directions. The first one is that of keeping certain pieces permanently in their collection; products founded on innovative concepts and created as part of their history of working with the Campana brothers Fernando and Humberto, with Masanori Umeda, Francesco Binfarè and Jacopo Foggini, of working with 'authors' as it calls them, authors and not designers.

Let us take a moment to think about these words. The word 'design' has been removed from the Edra vocabulary and again this is a challenge, in a society of appearance that often inappropriately applies the label “design”. Edra has removed the term despite having a full claim to belonging to that world.

Again, Edra uses the word 'author' to talk about its designers, bringing them into the artist's sphere and acknowledging their strong character of creative freedom, freeing them from the conditioning of marketing (another word removed from the company's organizational charts) that dominates in other places, The focus is on the role of the author, who dreams and draws, and then together with various profiles in the company, transforms ideas into products. As in the work of artist Emilio Isgrò, removing the unnecessary words from a text allows us see some underlying truths. One of these in Edra has led to the choice of using technology ownership to protect its unique assets, such as the "intelligent cushion" and Gellyfoam, which are both patented inventions, and carefully guarded company secrets.

To conclude, Edra is working to affirm a vision based on an idea of innovation and beauty that perhaps could only be realised in Tuscany, and this is where the genius loci returns. Tuscany is a land that, even before the Renaissance, gave central importance to Art, Invention and the Human: a place where the know-how of artisans has been perpetuated for centuries in a tradition of excellence in selecting and tooling fabrics and leathers.

For Edra having a vision means challenging time by looking into the soul of things, building objects for a lifetime and beyond. Which means to never cease dreaming, making and perhaps even flying. Because, as Leonardo wrote: "Once you have known flight you will walk on Earth looking to the skies, for you have been there and that is where you will desire to return".

|

Pierluigi Masini A professional journalist, with a degree in Italian literature and a specialisation in Art History, two master’s degrees in Marketing and Communication, he teaches Design History at Raffles Milano and Interior Design and Sustainability at YACademy. He is the author of a book about Gabriella Crespi. |