октября 2023

Maurizio Corrado

Beyond Vision

I'm writing on a day in mid-May in the year 2023. A time in which some people in the global village McLuhan posited in the 1960s have became aware of our united planet and looked behind them to see we are already in the aftermath.

The future has changed.

For a business to concretely develop today we must deal with the reality of the Anthropocene; and this is where visionaries come into play. There is one faculty that has saved us so far from the changes and crises we have faced in our existence as a species. It is called imagination and it is thanks to this faculty that we have imagined the tools we then created; from small chopper axes to the shuttle. Today we need this faculty, this ability to imagine, to produce visions. Designers must necessarily be visionary; they have a professional task to imagine the future, and to imagine is to design. This habit, of thinking about the future, brings the work of a designer closer to the activity of a visionary: one could say it is a variation on the theme. A pure visionary is not concerned with realising their vision, while for a designer this is the point of arrival: however what unites them is the departure, the vision.

It might be worth going back through the history of the project imaginary.

A famous painting called The Ideal City dating from the late fifteenth century by an unknown artist - though sometimes attributed to Piero della Francesca - represents both the recent discovery of perspective in painting, and the appearance it was imagined an ideal city should have: harmony, perfection and symmetry reign supreme.

One thing we notice, which is revealing if we read it in the light of modern architecture's development, is the absence of human beings. Human beings do not exist in this perfection, just as they don't exist in the twentieth century's idealist visions of modern architecture, which also draw on Platonic ideas.

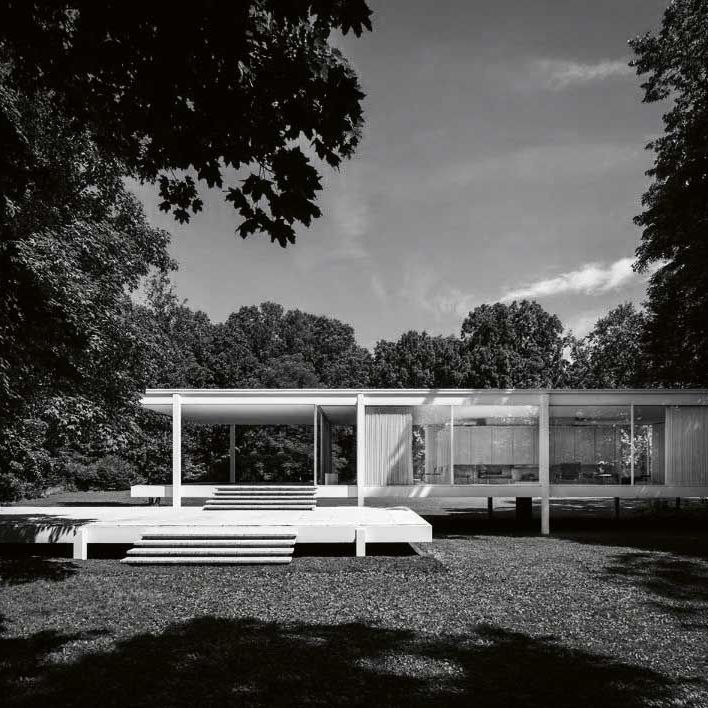

A clear example of this is the house created by Mies van der Rohe in 1951 near Chicago for Edith Farnsworth, his mistress, who after going to live there not only left him, but took him to court. Pure and clean, the house seems suspended above ground and is undoubtedly a masterpiece of Mies van der Rohe's aesthetic. Measuring 8.5 metres by 23.5 metres and raised on stilts, the building's interior functionality was reduced to the minimum and contained in an otherwise completely transparent body covered in light wood. Fantastic, if inhabitants were also transparent. But Edith wasn't, and she was determined to at least have some curtains. She claimed it was too hot in summer and too cold in winter: she even said it was infested with mosquitoes. Naturally nothing was allowed to touch the purity of the work, especially the unfortunate case of someone having to live in it. Mies indignantly refused the curtains and any other modifications, and the pair ended up in court. Since that time his house has become one of the most-loved and tragically imitated by architects.

In 1516 Thomas More published Libellus vere aureus, nec minus salutaris quam festivus de optimo rei publicae statu, deque nova insula Utopia, which we all know as Utopia. More's great merit was in finding the right word to define something that had been going around in Renaissance minds for some time, laying the foundations for development an imaginary that never died out, and that continues to produce effects. Beyond the work itself - which describes an island on which everyone works six hours a day and money and private property do not exist - it is the notion of an ideal place that took root deeply in the nascent modern western world.

The City of the Sun was written by Tommaso Campanello in the Florentine vernacular and translated into Latin in 1623. The City of the Sun stands on an impregnable hill: it is circular in shape and defended by an enormous wall that narrows to a spiral around a central temple forming seven circles. Four doors are positioned at the city's cardinal points, and at the centre is the Temple of the Sun with a circular plan. One of the features of this city is that the inhabitants practice the common sharing of goods and of a community of wives.

Reading and looking at the diagrams and representations of these ideal cities we cannot fail to be reminded of the geometric construction of Dante's divina commedia.

The seeds sown by the two Tommasos, More and Campanella, found fertile ground in the second half of the 19th century, in which the nascent needs of an industrial system were transforming cities in irreversible new ways. Strong ideas were necessary, and a new generation of utopians joined forces with the older texts to develop a new idea of city: they started the garden city movement. Their names were Robert Owen, Claude Henri de Saint-Simon and Charles Fourier. In a beautiful edition of the Teoria dei quattro movimenti. Il nuovo mondo amoroso (The theory of the four movements. The new amorous world) edited by Italo Calvino for Einaudi in 1971, Calvino privileged the visionary Fourier.

In his work we find a new society, re-invented down to the finest details and in which his sexual theories, which led to scandal, generate spaces and places his disciples tried to put into practice.

However what most influenced the imagination of architects' were his Phalanstères, or "grand hotels". These were buildings holding between 1600 and 2000 people, living together in a socialist sort of society conceived to be self-sufficient and without having to go outdoors, just like a contemporary mall.

In 1851 the First Universal Exhibition was to open in London and construction of the structure was entrusted to gardener Joseph Paxton. Perhaps not everyone knows modern architecture was invented by a gardener. Paxton had spent 48 years in the best gardens in England where, as well as being deeply knowledgeable about exotic plants, he also earned a reputation for being one of the best builders of greenhouses. Now he had the opportunity of a lifetime: he was commissioned to construct the edifice that would house the International Exhibition. Paxton didn't need to be told twice, and he did things in grand style. He designed and built an immense greenhouse 120 metres wide and 562 metres long. The building was colossal but its particularity was not its size. The fact is that for the first time, in order to build it, Paxton had developed a system of prefabrication. Crystal Palace became the principal symbol of the kind of functionality the Modern Movement began to preach a few generations later.

But the charm of the greenhouse is subtle and it pervaded the soul of Paul Scheerbart, a singular Polish writer who was intolerant of any form of work that did not take place at a table where he could talk and drink. In 1914 Scheerbart brought out a short book called Glasarchitektur or Glass Architecture. It was an illumination for architects. Crystal Palace had provided the technique ,prefabrication, and now Glasarchitektur supplied the philosophy. Architecture must be made of glass, transparent: life itself must be transparent, luminous and joyful.

The 1960s opened with all the arts at the peak of their activity and 'contamination' as a byword. In this climate, where pop art reigned supreme in painting and literature and cinema were interwoven, architectural culture was influenced more than anything else by science fiction and comics. The stories written by Philip Dick contain imaginaries that take us through the whole of the second half of the twentieth century up to the present day.

The entire radical architecture movement of the 1960s and 1970s was deeply immersed in the atmospheres evoked by cinema, television and comics - inhabited by Flash Gordon and Barbarella. The literature that always accompanies architects, and finds greatest fortune with them, is the literature of the visionary.

In his lovely book Design and Anthropology Gian Piero Frassinelli recounts how in Superstudio practically the only books that circulated were science fiction. Science fiction stimulated the world of cinema, and cinema produced images that influenced architects. Imagined cities and fantastical objects were an invaluable source for those who were concretely building the future, and characters like Jules Verne, H.G. Wells, Aldous Huxley, George Orwell and their successors created a reserve of potential ideas: above all in those years the winds of upheaval and freedom that blew through society also permeated the world of architecture and design.

Superstudio, Archizoom, UFO, Gruppo 999 and many others imagined possible other worlds, sowing seeds that are finally giving fruit today, in areas from relations with other living things to caring for the environment.

The Bolidismo movement of the mid 1980s was inspired by these ideas. By taking up the legacy of Futurism and joining it with American Streamline the movement overturned the decade's dominant design aesthetic and offered a vision that proved prophetic. "The bolidista strives for immobility and simultaneous presence in several places" together with the vision of Fluid City, defined as "an ensemble of contacts without physical limits" are exact description of everyone's daily life today, with computers, internet and cell phones.

The fluidity coined by Bauman in relation to society is symbolically represented in Edra's furnishing project by the dynamism of form in works like Tatlin, designed in 1989 by Roberto Semprini, exponent of the Movimento Bolidista, together with Mario Cananzi .

In the following decades Radical Architecture developed in ways that led to some of the design world's most interesting proposals. Massimo Morozzi, one of the minds behind Archizoom, worked for years in the design system looking for new designers around the world, and stimulating them to produce some of the most interesting and innovative work in projects that have become true icons. In particular, in his work as an art director, Morozzi found in the Edra company the right terrain for seeds sown during his Radical Architecture years to flourish, sometimes literally, as with Umeda Masanori's projects.

Very soon the architectural world and design system will have to face up to something essential: changes that have come about during the Anthropocene are not only related to natural landscapes and to cities. Literally everything is changing: the economy, how we think and create culture, our very vision of the world and the place of human beings in the universe. The advent of an Anthropocene imaginary has transformed time, and all the rules and scenarios we have worked with until now are suddenly obsolete: sooner or later we will have to take note. Only since the start of the new century has there has been an acceptance of design approaches that take account of what is now called environmental impact.

The question is: what should a project do in the Anthropocene era? Today we need to imagine scenarios, and give answers, using our imagination and vision.

|

Maurizio Corrado Architect and curator, Corrado has been involved in project ecology since the 1990s. He has worked for newspapers and television, curated design programs for Canale 5 and SKY, organised exhibitions and cultural events, directed series, magazines and training structures, and published over twenty books on design and ecological architecture, with translations into French and Spanish. He directed the Italian/English magazine “Nemeton High Green Tech Magazine”, and has taught at the University of Camerino, Naba in Milan, and the Academies of Fine Arts in Bologna, Verona and Foggia. With the Italian Cultural Institute in Melbourne he is curating a project that won a tender from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for the creation of a festival of Italian culture in Melbourne in 2023. He writes literature and theatre. |