“An Allegory with Venus and Cupid” Agnolo Bronzino, 1540-1545, National Gallery, London.

сентября 2024

Chasing Kairòs

If the theme of time is raised so often in advertising communication, it must mean it is a central subject of our lives.

I would like start here, with some examples.

In a television advert for insurance, we hear the voice of a CEO, walking among chess pieces as big as people, explaining that yes, we must take care of our pawns, rooks and bishops, but that, in the end, time is the determining factor.

I watch the film advertising an online bank, and inviting us to think about our children and grandchildren's futures.

Turning the pages of a newspaper I come to one with an anti-aging cream, focussing on the signs time leaves on our skin.

In a bookshop window I am struck by a famous dietician's book, promising to halt the progress of time.

The concept is longevity, time stretching, the myth of youth: the truth is, the older we get, the more we like to feel immortal.

Again, a region in Italy, famous for its mountains, invites us to visit and "rediscover time".

And to conclude, an exhibition of work by a renowned photographer of celebrities, black and white images of divas in poses from the past, bears the baffling title, Timeless Time.

Timeless as a concept has been around for years in fashion and design. Timeless is everything that never goes out of fashion, a "magic" label applicable to furniture, lamps, kitchens, mattresses, and even tiles and taps. Timeless is a flavour that goes with everything, like vanilla ice cream, or beige clothing. But the things that really are timeless do not need certification. We know that.

It is clear at this point that marketing likes very much to use the time concept: it is evocative, picks up on aspirations, insightfully probes the latest concerns, wards off fears. In short, it touches deep chords and urges us to purchase a thousand different products. Our human relation with time is a fascinating and unresolved issue that has been with us for millennia, a theme that has taxed philosophers, scientists, writers, artists and poets, even saints and, inevitably, sinners. It is one of the great mysteries we have to deal with.

My background in art history reminds me of certain works where the concept of time is fundamental, and I want to offer a contribution starting with these.

To begin with, the An Allegory with Venus and Cupid by Bronzino (1540-1545) at the National Gallery in London; a painting that has always been emblematic of sensuality, studied on different analytical levels and for its iconographic meaning. History tells us that Cosimo I, Duke of Tuscany at the time (and not yet Grand Duke) had the painting sent to Francis I, King of France, to ingratiate himself and form an anti-Habsburg alliance, given the expansionist plans of Charles V.

But in the painting, commissioned to Bronzino, things are not quite as they seem. In the foreground we see a kiss, far from modest, between Venus and Cupid, who actually turns out to be her son in the Olympus registers, depicted here in a lascivious pose to say the least. He touches her breast, while taking a diadem from her head. Seemingly enraptured and in the ecstasy of love, she instead is intent on removing an arrow from his quiver. These two figures are surrounded by several others, and on closer inspection we see we are witnessing an enormous deceit, a collection of lies, things that are very different from appearances. The feet of a young man on the right, carrying flowers, and dancing with a smile, are being pierced with thorns as he walks. A girl behind him with an ethereal face has several features out of place: the body of a snake, the paws of a lion, hands in the wrong place (her right hand is on the left and vice versa) she holds a honeycomb in one, and a scorpion sting in the other. Sweetness and poison.

To the left of Cupid, a woman howls, her hands raised to her hair: she is probably a personification of Despair after sensual love. At the top left of the painting, another female figure, Madness, fights an elderly bald and bearded man for a large blue drape that forms the background of the painting. This man has wings and an hourglass on his shoulders, and represents Time. So here we come to our theme. To all intents and purposes this is the man truly at the centre of the scene. He pulls his cloak to him, and the moment he manages to pull it away from Madness, and gather it to him, this whole series of deceptions, the languid and amorous transport hiding games of betrayal, will suddenly come to an end, swallowed by time.

It's a nice message from the Duke to his potential ally! I'm sending you this painting of sensual love, but be careful, because things are never as they seem. I can be sweet, but terrible too. You have been warned. Time will see justice rendered.

I'd like to stay on the subject of time with a work Titian painted a few decades later: the Allegory of Prudence (1565-1570) in National Gallery of London. Here we see three male heads of different ages with, below, three animal heads. A Latin inscription referencing time runs above the portraits: “EX PRAETERITO / PRAESENS PRVDENTER AGIT / NI FVTVRA(M) ACTIONE(M) DETVRPET” which translated reads: from experience of the past / the present acts prudently / lest it spoil future actions. Titian painted this work when he was around eighty and could see how his life had unfolded. It is a sort of family will, showing Titian in old age as the past, at the centre his son Orazio, who at the time was his assistant, and on the right a young grandchild Marco Vecellio, the future. But what of the three animals? These are a reference to scholarly texts fashionable in Venice at the time, in which the wolf feeds on memories of the past, the lion is a symbol of the strength that helps give direction to the present, and the happy, carefree dog leads us to a future of pleasant things.

Titian is not only a painter but also a scholar, the friend of writers like Pietro Bembo and Pietro Aretino. He is fascinated by the subject of time, which he had already painted in The Three Ages of Man (1512) in Edinburgh's National Gallery of Scotland, and before that in The Old Woman (1506) in the Gallerie dell'Accademia in Venice (Erwin Panofsky attributes this painting to Titian, and not to Giorgione). In this last portrait the signs of aging are shown without pity. The woman holds a scroll in her hand, “Col Tempo” (with time) which leaves no doubt. It is a sort of memento mori.

Titian references a linear vision of time, the same vision we have now conserved for five centuries. A straight line, with the past on the left, the future on the right, and in the middle the point where we are. But time has not always been depicted in this way. When Christ was born, in year zero, we began counting time in the particular way we know. Before this, representations of time were circular, reassuring alternations of seasons, self-sustaining energies often represented in the Ouroboros, the snake biting its tail, an element of iconography found in vastly distant civilizations from Central America to India.

To now we have looked at subjects in art. We started out with marketing, which aims to sell, and now we come to science, which aims at objectivity. We have changed levels. These linear representations of time remind me of reflections by Carlo Rovelli, the theoretical physicist and exceptional thinker who for decades has put time at the centre of his research. Rovelli introduces us to verified data regarding time's changing nature. For example, time passes faster in the mountains and more slowly in the plains. Interstellar, the 2015 Oscar-winning film, shows a father returning to Earth after 124 years not having changed at all, to find his daughter, now aged 90, looking every day her age. Another now verified concept is the variation in time related to speed, which means a clock travelling at high speed on a plane marks time more slowly than the same clock on the ground.

But the most astonishing part of Rovelli's reasoning is his idea that the dimension of time, more than anything else, is personal. An objectively fixed past, a hic et nunc here and now present, a future to be explored, do not exist. It is all false, an approximation of an approximation of a much more complex reality, related to the concept of entropy. In reality, theoretical physics explains, time has an order, but the order is not linear, rather it is determined by gravitational fields. And if we add quantum spacetime then we must imagine our existence as immersed in a sort of gelatinous time of the Universe. In short, we are minute entities at the mercy of forces we do not know.

So, in the end then, what is time? Let me quote Rovelli verbatim, “we begin to see that we are time. We are this space, this clearing opened by the traces of memory inside the connections between our neurons. We are memory. We are nostalgia. We are longing for a future that will not come. This clearing that is opened up in this way, by memory and anticipation, is time, a source of anguish sometimes, but in the end a tremendous gift." (The Order of Time, 2018)

I am fascinated by this definition that floats our being-ness in such a delicate way.

And leaving Rovelli, I'd like to stay with this reflection on time as a personal dimension that he has felicitously brought us to, and return to my memories of studying the classics. In the Greek language, time had more than one meaning and was expressed through different words. Chronos or Χρόνος was used to indicate a quantitative dimension, the sequence and flow of things, of objective data that could be measured. But when the Greeks wanted to talk about a more personal dimension in a more intimate way, a benevolent, pleasant moment that was auspicious, opportune or happy, they used the word kairòs or καιρός.

Chronos and kairòs. I ask myself: why have we lost such an important distinction in modern terminology? Why did we not hold on to the desire to describe a time we take out from the daily repetitive life of things, of office work and the roles we take or that are assigned to us, to indicate a time just for ourselves? A time for reflecting, for enjoying the things we like most, a truly timeless time, passing slowly, without anxieties, masks, and schedules? A time that does not oppress us, or press us, but that is on our side, benevolent towards us, bringing us beautiful things?

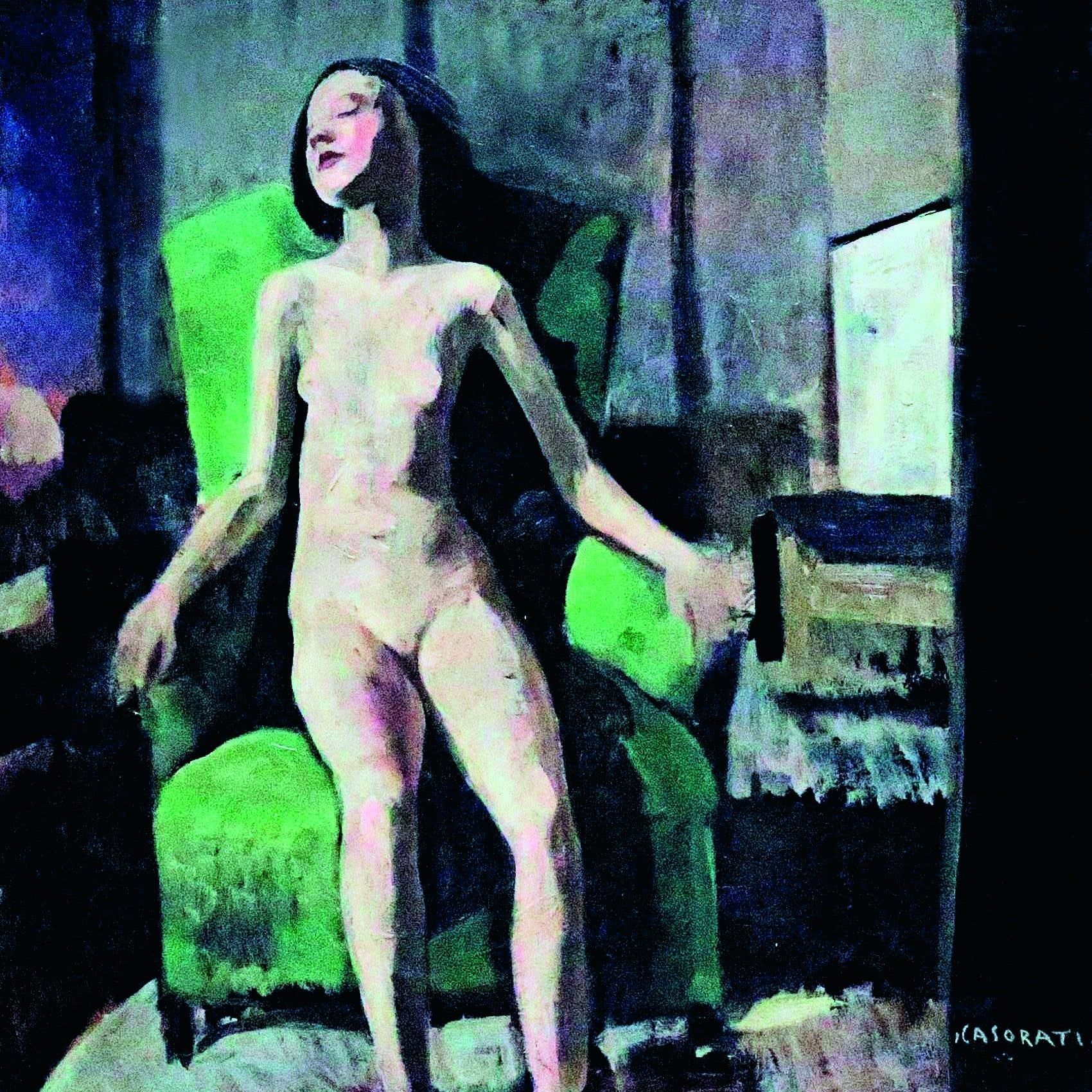

Kairòs is the representation of time I see in Seated Nude (Green Armchair) a small work by Felice Casorati painted in 1919 and now in Milan's Museo del Novecento. It shows an adolescent girl at home, her unclothed body intimately depicted on an armchair that welcomes her, her hands relaxed and resting on the armrests, her face turned to one side, her expression dreamy. She's imagining how the life she has ahead of her will be. She is experiencing the quality of time, protected by the embrace of a soft comfortable cocoon, where she can be herself. Where she can show herself as she really is. She is savouring her personal space-time and has chosen to present herself to the painter with nudity that is anything but sensual. Because she has stripped away her roles and conventions, thrown down her clothes and mask. This nude is a classical abstraction, the longing for perfection and freedom, a dimension completely removed from reality. It represents a different level, a state we strive towards, and an invitation to seek it out. Redemptive abandon.

This, for me, is the visual representation of Kairòs. Time for ourselves, only for ourselves. Truly timeless.

|

Pierluigi Masini A professional journalist, with a degree in Italian literature and a specialisation in Art History, two master’s degrees in Marketing and Communication, he teaches Design History at Raffles Milano and Interior Design and Sustainability at YACademy. He is the author of a book about Gabriella Crespi. |